m3architecture’s climate-positive Olympics proposal in AFR

An article in the Australian Financial Review on 26 September 2022 questions the Queensland government’s commitment to delivering a climate-positive Brisbane 2032 Olympics and uses a proposal by m3architecture to show how we could do better. Thank you to the AFR’s Michael Bleby for penning the well-researched article, which we reproduce here.

m3architecture cares deeply about our city and about climate-positive design. The purpose of our proposal is to demonstrate that it can be achieved and to generate a public conversation.

Pulling down Brisbane’s Gabba for the Olympics is a bad idea

by Michael Bleby / Australian Financial Review / 25 September 2022

The Queensland government is pushing ahead with plans to replace Brisbane’s Gabba stadium for the 2032 Olympics even as architects warn that demolishing and rebuilding the sports ground will blow out both the Games’ carbon footprint and its $1 billion budget for a new flagship venue.

The Palaszczuk government has contracted consultancy Populous to come up with a reference design – not the final design, but a preliminary process to determine the features it will need and how much a new stadium is likely to cost – which will guide the formal tender.

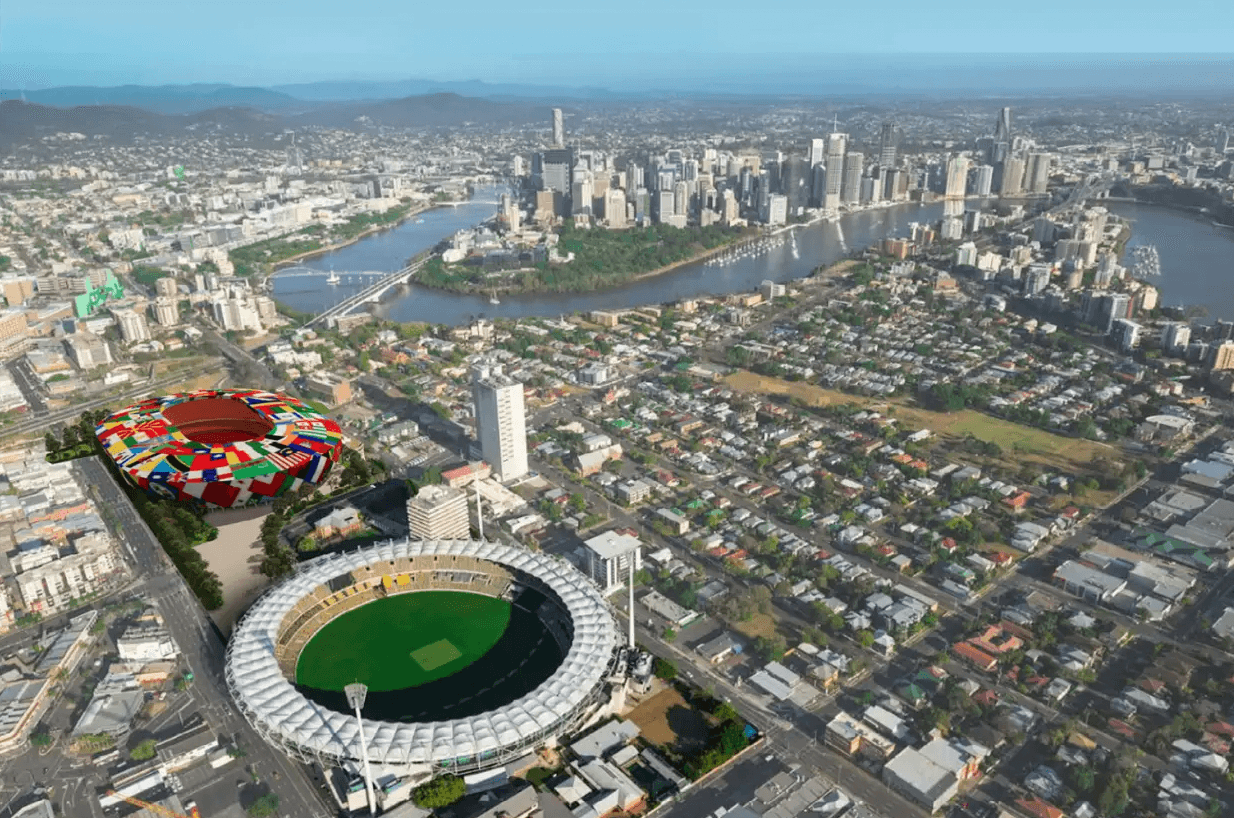

Flagging a different plan: Instead of demolishing the Gabba and building a larger stadium in its place, the Gabba could serve as a warm-up venue for the Brisbane 2032 Olympic Games and a temporary Olympic stadium, designed to be taken apart afterwards, could be built on the old Go Print site. m3architecture

But plans for Brisbane 2032 for 84 per cent of venues to be existing or temporary, are already less ambitious than Paris 2024, which has an equivalent figure of 95 per cent, or Los Angeles 2028, which claims 100 per cent of buildings will be reused or adapted.

And the mega-project, which Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk last month said was “locked in”, would make the stated goal of Brisbane 2032 being the first “climate positive” Olympics even harder to achieve, said David Baggs, an architect and sustainability consultant to the Sydney 2000 Games.

“For it to be climate positive it has to take missions out of the air. It has to negate all of the existing emissions the Games creates and take out more than the Games need to take out to be carbon neutral,” David Baggs said.

The new stadium idea went directly against this goal, he said.

“There’s a huge amount of energy just to take it down plus the impacts on the heritage around it and then you’ve got to turn around and rebuild it.”

Populous, an architecture firm specialising in sports stadiums – including Metricon Stadium on the Gold Coast, Sochi 2014’s Fisht Olympic Stadium and the Ice Ribbon National Speed Skating Oval for this year’s Beijing Winter Olympic Games – referred questions to the government.

Definitions are often rubbery in the world of Olympic Games, and making like-for- like comparisons of the carbon footprint of Olympic Games is difficult, as organisers use their own definitions.

In the case of LA2028, for example, organisers themselves are building no new buildings, but three privately owned sports venues – including a stadium – are under construction, but will not be included in the official carbon calculations, Mr Baggs said.

The Queensland government’s own public documents don’t list the Gabba project as one of six new venues planned for 2032, but rather on its list of eight venues to be upgraded.

The 126-year-old Brisbane Cricket Ground can’t serve as an Olympic stadium. Its 42,000 seating capacity is less than the 50,000-60,000 the Olympics requires and its round shape doesn’t suit the standard athletics track.

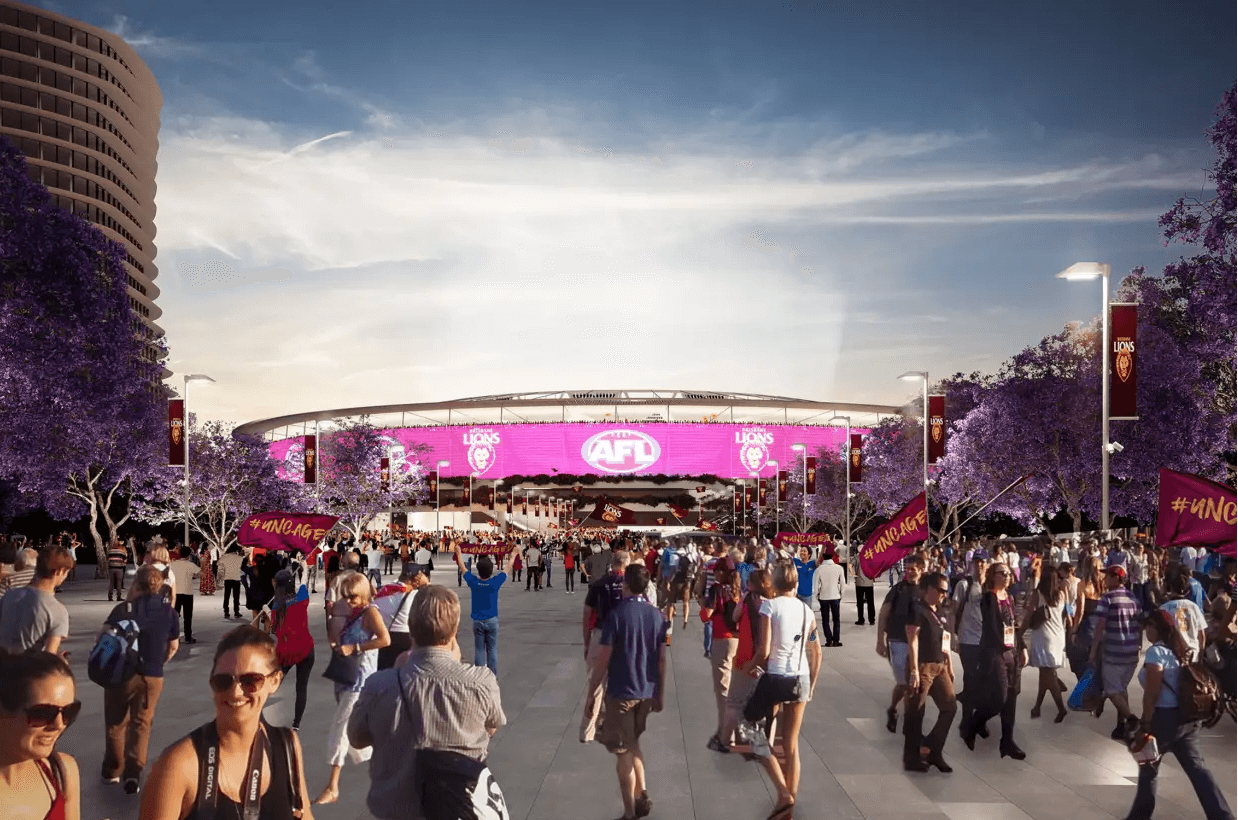

Scoping work: The Queensland government says rebuilding the Gabba is locked in. Queensland Government – Artists’ impression

Olympic Games are notorious for blowing up budgets. Former Australian Olympic Committee president John Coates, a key driver of Brisbane winning the 2032 event, has insisted that costs would remain under control. But history suggests otherwise.

“It’s extremely likely to be substantially greater than $1 billion, taking into account the dimensional challenges,” said Mark Jones, an associate professor in the University of Queensland’s School of Architecture.

Constrained by Vulture Street to its north and Stanley Street to the south, a rebuilt, larger Gabba would rise up over both roads and this would be pricey, said Dr Jones, a past president of the Queensland chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects.

“You can’t have columns coming down on to the road,” he said. “It means very significant cantilevers … It’s going to be an expensive solution.”

Some industry figures said such a project could cost $2.5 billion.

The government said final costings would be determined by the reference design process under way and on Sunday Transport and Main Roads Minister Mark Bailey said all options for stadium were being “fully explored”.

“The Gabba is the Olympic stadium and will be the Olympic stadium,” Mr Bailey said. “This is a great opportunity to refit it or to rebuild it, whichever is the most economic.”

But there are alternatives. Brisbane-based m3architecture proposes retaining the Gabba in its current form as a warm-up facility for the Games and building a new temporary stadium – designed to be dismantled after the tournament – on the former Go Print site at Woolloongabba.

When it’s over: The space used by the temporary stadium could be returned to parkland or other uses after the Games. m3architecture

The 52,000-square-metre site currently used in construction of the underground Cross River Rail Woolloongabba Station, comes back into public use in 2024 and won’t have complications of the heritage-listed East Brisbane State School and former Woolloongabba Police Station on the Gabba site, m3architecture director Michael Lavery said.

Mr Lavery said his uncosted proposal would be quicker and cheaper than a knockdown and rebuild of the Gabba. It would also be cleaner from a carbon- emissions perspective, he said.

“The Gabba was never designed to be deconstructed. The best you can do is take it apart, cut it up and potentially recycle the steel,” Mr Lavery said.

“But when it’s designed to be deconstructed, all the component parts are made to be reusable in other standard forms of construction.”

Michael Bleby covers commercial and residential property, with a focus on housing and finance, construction, design & architecture. He also dabbles in the business of sport. Michael is based in Melbourne.